by Laurie Macfee

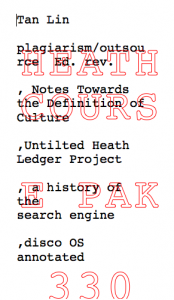

Heath Course Pak

Author: Tan Lin

ISBN: 978-1933996271

Publisher: Counterpath Press http://counterpathpress.org/

Dec 15, 2011

2nd ed, revised

$17.95

Were you to pick up Tan Lin’s seminal little book Heath at your local bookstore (and may I suggest that if you find it, you buy it immediately), you might take it at face value. It is a 3/8th inch thick soft back, with no page numbers. The cover features the title in red caps, HEATH COURSE PAK RFC. Layered behind that, in black text, is Tan Lin’s name followed by: “plagiarism/outsource, Ed. Rev., Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, Untilted Heath Ledger Project, a history of the search engine, disco OS annotated”.

A quick perusal between the covers will net you the following: it is a book, “set” in plain text (or a courier-esque simulation), a mash up of data sources from RSS (Rich Site Summary) feeds to blog posts, Google searches, retrieved photographs, handwritten notes, redacted text, sticky notes, an interview, annotated text, meta text on design of the book, etc. A disjointed amalgamation, it is written in multiple parts, the most obvious of which are Part 1 Samuel Pepys and Plagiarism, and Part 2 Outsource. But even on a cursory glance, the textual layering posits more “parts” to this book than the noted two.

On the surface, this book appears to be a collage about the actor Heath Ledger’s death in 2008 of an accidental overdose. At one point, Tan Lin even appropriates the minute-to-minute news feed and blog reporting Ledger’s death. There is an autographed fan photo of Ledger on the Broke Back film set, but also one of Jackie Chan in an ad selling Green Tea. As Alice said, “Curiouser and curiouser…”

At this point, two things might occur. First, a reader, aka a “user”, might thumb through the book blindly and try to make some sense of it: dip in and out of the text stream, turning the page when bored, jumping, subverting the authorial intent. Or is that part of the authorial intent? It is at this point that the questions may begin: Does the author intend for the reader to make her own meaning, a personal grammar? In this way, is the book democratic, perhaps even Marxist, as we upset the power and production of authority? Is that part of Tan Lin’s aim with the sub-title “Notes on the Definition of Culture”: our relaxing attention spans, the temporal nature of information and language in the current zeitgeist? And what is the deal with Jackie Chan? Which leads to the second option: as the reader becomes confounded by the surface, she might return to where she started, and try to untangle the web that is merely the title, let alone subtitle, on the cover.

PART 1: TEXT

Grammar is the set of structural rules that governs the composition of clauses, phrases, and words in any given natural language. – New American Dictionary

A cloud of philosophy can be condensed into a drop of grammar. –Ludwig Wittgenstein

One way of looking at Heath is as a game, a form of serious play, with the end user as sleuth. If it was digital book, written in hypertext, we could jump from node to node, accessing information. But when readers hold the paper book in sweating palms and are faced with a proliferation of language/data, the notion of interactivity changes. Luckily, from the moment we pick up the book, Tan Lin has set the conditions or grammar for reading it. He has designed the environment for us, if we choose to “interact”. To this end, the cover offers key ways we might begin to understand the text. Armed with my computer, I decided to parse it, to see where it led, in consideration of the contents.

First, because Tan Lin chose to replicate the language of programming as the primary type on the cover and throughout the book, we are notified that we are entering into a world of the data stream. This font is shorthand for the constructed language of technology, where layers of information produce/hide/create/numb meaning. In addition, the title words fall apart on the page, as words do in plain text, creating a disjunction, a level of abstraction.

The first word of the title, HEATH, is our first hint that this is about Ledger (though without opening the book, it could be about the Scottish highlands). Upon realizing the connection with the actor, we might remember that his death was a cause celebre and, as the book notes, over 25,000 stories were produced. His death becomes a perfect catalyst to talk about the cultural simulacra of imagery and text, the way global obsessions light up RSS feeds. This very real tragedy became consumed, a spectacle of representation, a mediated cultural icon producing layers of meaning. We could choose to tap into or ignore the proliferation. Included in the book is a photocopied prospectus of a paper written about the first edition of this book, which mentions actor network theory, or ANT. ANT treats objects as part of social networks – mapping relations between materials and concepts. Ledger’s death is almost a rebus, a pun, for ANT: an actor, whose death becomes the relational material for an entire network of responses, which become a theoretical poetry.

A COURSE pack is a set of materials arranged by a professor to be used in the classroom, including copied articles or portions of books. The packet is a multi-authored compilation, a low-tech aggregation. It is cleared under the Copyright Act of 1976 as fair use, in the educational context only. Tan Lin changes pack to PAK, another technological reference and play on language of software. PAK is a file extension (similar to doc or pdf), an abbreviation of “package”. By titling this book as a COURSE PAK, Tan Lin is signaling that it is a fair use aggregate of technological language. I sense the humor in this, as well as staking ground.

RFC is tech lingo for a “request for comments.” Is the author prodding us to interact, or merely toying with the Internet specifications and protocols for procedures and events? If this is indeed a course pack, is Tan Lin telling us the readings are up for discussion?

PART 2: SUBTEXT

Below Tan Lin’s name, we come to the first part of the subtitle, plagiarism/out source Ed. rev. In the text, Tan Lin complicates authorship by plagiarizing himself (lectures, notes, poetry) as well as outside sources, including Google’s Project Gutenberg. In Part 1, he begins with PG’s representation of Samuel Pepys diary. Is Google’s offering of this primary source plagiarism or access? As an aside, the original diary was written in shorthand, a code, just as this book is written in a form of shorthand, requiring translation.

Tan Lin’s use of the word outsource denotes the contracting to a third party, such as news blogs, RSS feeds, etc. It may also point to the fact that part of the text was generated in an Asian Poetry Writing Workshop he led. It could even point to a political connotation of contracting public services to for-profit corporations. Regardless, this use of a multi-authored texts points to how we gather information, how language is shared contemporarily in digitized form. Because this is titled a course pack, Tan Lin plays with notions of appropriation, copyright, and censorship – major issues in the age of digital language. A portion of the text, as well as a sourced photo, links to the nature of derivative ecstasy. Finally, I find the Ed. rev. portion to be amusing – a tongue in cheek signifier that this compilation has in fact been edited, and revised.

The second part of the subtitle, Notes on the Definition of Culture, brings questions. Is an RSS feed a manifestation of collective intellectual achievement, a form of art? Or is it more related to the scientific notion of a culture, an artificial medium that promotes or cultivates replication? At base, is culture a noun or a verb? With technology, is culture a metaphor for how we experience language: remixed, random access, temporal, aggregated, unauthored? How does this affect the audience? In the same way that a repeating sound pattern will lull the eye, does this language of inundation bring on a hypnotic state of mind, which we sometimes call boredom, or numbness, or brainwashing? What happens when we are bored by someone’s death? Is technology neutral or a benign instrument in the construction of culture, one that can be used well or badly, like a gun?

When reading Untilted Heath Ledger Project the brain automatically auto-corrects Untilted to Untitled. This might be a humorous reference by Tan Lin to how fast we type, or the fact that we expect the computer to correct us, or our brains to make sense of nonsense, while also defining the HEATH of the title. However, if tilt means to unsteady, lean, slant, or cause to topple, then untilted means steady, rise, ascent, increase or agreement. Read with authorial intent, the wording walks both lines – humor and information.

Tan Lin gives us another clue with the subtitle, history of the search engine. It is a short history. From its inception in 1990 with Archie, to Google’s birth in 1996, to Bing in 2009, the ability to search word streams on the World Wide Web has been sculpted into an art form. In the beginning, users had to enter exact wording, so if you wrote “untllted Heath Ledger Project” into a search engine, nothing might come up. By the time Google came on the scene, with autocorrect and its authorial relativity linked to the number of people visiting a site, questions of language ownership began to rise. Search engines have led us, in 23 years, to the advent of data mining, inexhaustible data horizons, real time information retrieval, open directories, rich source sites, indexing and architecture of information, retrieval index design, permanent storage and retrieval of natural language documents, web crawling, news feeds. Search engine’s revolutionary effects on culture cannot be underestimated: a constructed hyper-reality of hypertext, shared meanings, interconnected with no dominant axis of orientation.

The part of the subtitle that might cause the most initial difficulty is disco OS. What does a dance style have to do with an operating system? Using the ubiquitous search engine, I found two things that shed insight. First, disco is an app that allows you drag, drop and burn info onto discs, and then to instantly search thousands of files across discs. Perhaps Tan Lin used disco to organize the information streams in the book? But then, I found an essay on the website Project Muse, penned by none other than Tan Lin in 2008, called Disco as Operating System. It linked the generic cultural dance phenomenon and its “mimicked forms of mass cultural production” to the digital age of programmed language we are mired in. It is a brilliant essay that shed light on production of the book. These passages seem to presage the blanketing of Ledger’s death as noise across the blogosphere, and Tan Lin’s reaction.

Suddenly disco was everywhere, a product without clear origins, broadcast indiscriminately like Tennyson’s and Longfellow’s trance-inducing poems in the nineteenth century or home décor in the post-Bauhaus era….

Inverting Claude Shannon’s theory wherein increased information generates greater noise, disco would blur the distinction between signal and noise….The listener experiences disco desiringly, without listening and blindly, as a function of increasing uncertainty in the remix, where the listener is the output—that is, a programmed state of mindlessness…In this sense, disco exposes even as it camouflages desire as a programmable function.

And so the social world of language production and meaningful utterances is rendered obsolete and automated.

Such a programming language was once called literature (we have chosen to call it art history), though disco, of course, is not a literature at all; it merely simulates the effects of literature (as empty brand) with the uncanny precision of our era’s version of a lullaby: the remix. Disco is a programming language…

In our era, unlike in Shakespeare’s, all plagiarism is part of an operating system. …most writing is automated and invisible, an empty form of surface decoration where “writing” is the instantiation of a software code being transferred from one location to another in an act of self-plagiarization.

Disco provides impetus for new modes of being and nonbeing involved in the writing and in particular the nonwriting of poetry and art, where lyricism, subjectivity, and personal expressiveness might be reduced to blips in an ambient sound track, where historical markers (of cultural products) could be erased, and where nonreading, relaxation, and boredom could be the essential components of a text. Poetry—and here one means all forms of cultural production—should aspire not to the condition of the book but to the condition of variable moods…

Tan Lin plagiarized and annotated himself in writing disco OS into the subtitle, and created a primer for the production of this text. Which brings us to the final word, annotate. Tan Lin points to the fact that he is making comments – he is making a mark. An antonym of annotate is gloss – a translation or explanation of a word or phrase, but also a glitzy reminder or link to the stardom of Ledger. To annotate something is to pay attention – this book is a sustained, voluntary attention, or a continual returning, to its object.

PART 3: FORM

Once I was finished parsing the cover for clues, there remained one question: why a book? A book is a carrier, an information repository. Tan Lin did not choose a tablet, or scroll, or an electronic book, but specifically a codex to carry the language of the digital age. A codex is composed of many little books: leafs of paper, folded into signatures, bound on one end (the spine) between two covers, it appears as one coherent whole. Tan Lin forced this treatise on multi-authoring/multi-languages into one single platform of exchange – data integration, reconciled representations. If language is a system, a social network, he placed his mash up of digital mayhem in one of the oldest analog information contexts in western civilization, the book. The codex offers compression and portability. We expect linearity, a beginning, middle and end, which Tan Lin subverted beautifully. He replicated the temporal experience of being on a computer (multiple tracks to read, linking non-cohesive fragments, electronic narratives) in an object that can sit on a shelf for a lifetime-one that can be accessed with no electrical components except human impulse. In the midst of all the abstraction, there is an ounce of hope in that action.

Is this book poetry? Literature? Book arts? Heath most definitely is an artist’s book, a meditation on our mediated reality in the early 21st century, how we experience the world, or a death. In an interview in Rhizome, Tan Lin noted, “Human remembering has become impossible.” Hopefully, in explicating the grammar or philosophy of the cover, this blog post lends a small insight to the poetry of memory constructed inside. Paul Valery said a poem is “a prolonged hesitation between sound and sense.” In that way, I believe this project is a vast language poem based on a prolonged hesitation between signal and sense. Tan Lin created a rebus, or perhaps Wittgensteinian language game, with this project. He has woven portals into pages of meaning, and bound the fleeting. You could spend an hour, a day, or a month lost in this portable rabbit hole.