“We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others,

that in the end, we become diguised to ourlves.”

-Francois De La Rochefoucauld

Review by Courtney Berti

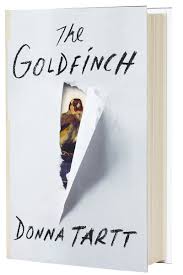

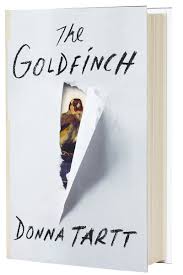

Donna Tartt

The Goldfinch

Little Brown

ISBN 978-0-316-05543-7

Why would anyone want to read a novel about the typical American teenager: after his mother dies, a promising thirteen-year-old moves in with his gambling drug-addict father, falls in with the wrong kids at school, does drugs, becomes an alcoholic, grows up, repeats father’s mistakes…It sounds like the plotline for a dramatic television series for teenagers. But the truth is that Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch is less for an uninformed teenaged audience, and more for a jaded and cynical adult audience. How does one figure?

Written from the first person perspective, readers are plunged inside the head of thirteen-year-old Theodore Decker at the moment when his upright, stable, fairly happy world is turned upside down forever. Initially, we see Theo making his first bad decision with his friend Tom, leading him to be suspended. His mother is escorting him to school to address the suspension and his behavior with his teachers when they are caught by a rainstorm. The two of them duck into The Hague to take shelter, browse for a bit, and in the moment we are introduced to the subject in the title (The Goldfinch, a painting by Carel Fabritius 1654) an explosion occurs that kills Theo’s mom and brings him face to face with fate in the form of an older gentleman by the name of Welty. Welty, in his last moments, gives Theo a ring that later leads him to an antique shop where he meets a lifelong friend by the name of Hobie who remains for Theo, and readers, a stable moral compass throughout the rest of the novel—a necessary character for a novel that tries to tackle questions such as: What is good or evil? Does fate exist? Is there a god? Does any of it mean anything?

It is in the stating of these questions, and in the stylistic choices that Tartt makes, that a number of risks are taken in the realm of what constitutes literature. For example, the twists of fate and the surprisingly happy ending are what have led more than one reviewer to identify (and criticize) The Goldfinch as Dickensian, in nature. Stephen King goes so far as to call Theo a “21st century Oliver Twist…” The criticism is that all of the loose ends of the novel are tied in a nice neat bow in a manner typical of Dickens as well as pop fiction and genre writers—pleasing to the unlearned reader of fiction but infuriatingly predictable to the student and writer of literature. In her essay, “The Breakout Element: Unpredictability and the Novel,” writer Lan Samantha Chang calls this neat wrap-up, “resolution of plot, at the expense of characters.”

Because of this tendency to break away from character for the sake of resolution, the end of The Goldfinch is, perhaps, the most notable risk taken by Tartt. The narrative style of the last chapter of the book changes drastically so that the main character, Theo, and his friends are indirectly addressing the reader while the characters are basking in the reverie of disasters righted and lessons learned, very much like the end of A Christmas Carol. In some cases Theo actually does address the reader (who he, ironically, suspects does not exist) but a good example of the tone near the end is when his best friend Boris says, “And I know how you think, or how you like to think, but maybe this is one instance where you can’t boil down to pure ‘good’ or pure ‘bad’ like you always want to do—? Like, your two different piles? Bad over here, good over here? Maybe not quite so simple” (745).

It may be that Boris is challenging Theo (and readers) a little too bluntly to abandon strictly black-and-white thinking (along with all the other little things the reader is asked to think about), as if the lesson of the book was not already learned by readers in the telling of it. Perhaps this is why some critics will call it a masterpiece like the artwork upon which the story is based, and why other’s will call it a children’s book for adults. Only in children’s books is the underlying lesson so tediously re-stated, but I think that Tartt pulls it off. The happy note on which the book ends is exactly what is needed as the reward for the reader who has experienced so much misery along with Theo for ten years of his life and at least a couple weeks of our own.

Not to say that the book is a miserable read, by any means. Tartt manages to draw readers so completely into the psyche of Theo via long, meandering, almost stream of consciousness paragraphs that we are sympathetic with his cause and feel as tortured as he throughout the novel. While this doesn’t sound particularly fun, I would argue that Tartt takes a risk by daring readers to explore the uncomfortable places of one’s own consciousness by writing in the first person, but also by creating a highly introspective, philosophical character who feels separated from the goings on of his everyday reality.

For starters, the book is divided into separate sections with their own labels, indicative of Theo’s emotional climate contained therein, (i.e. “Morphine Lollipop,” or “Wind, Sand and Stars,”), and Tartt manages, through her writing, to help us make sense of why each section is labelled as it is. For example, in the chapter entitled, “The Idiot,” we see Theo talking to himself: “…I hated being around people, couldn’t pay attention to what anyone was saying, couldn’t talk to clients, couldn’t tag my pieces, couldn’t ride the subway, all human activity seemed pointless, incomprehensible, some blackly swarming ant hill in the wilderness, there was not a squeak of light anywhere I looked, the antidepressants I’d been dutifully swallowing for eight weeks hadn’t helped a bit, nor…” etc.

Upon further examination, one sees that the title of this chapter (and its contents) is a criticism of modern American culture, which Tartt shows us throughout the novel—from New York to Las Vegas she uses pop-culture, art, film, and literature references to show their impact on Theo’s psyche. His choices and responses to this culture are demonstrated through his highly-conscious, deeply poetic, and philosophical persona.

Like this passage in which Theo is harried in the thrum of typical, every-day life for possibly the first time since he was thirteen, we see that it is not only the chapter headings, but the style of these long and winding passages, which are carefully crafted to reflect Theo’s state of mind. I believe that this is why, initially, the book feels slow and drawn out—reflecting a young boy’s half-stunned half-dead state of grieving almost too closely without giving any sense of a way out. But, once the story gets rolling and the reader is allowed to feel some relief along with Theo when he meets his friend Boris, these passages start to feel more natural, and then, dare I say, more like the stream of one’s own thoughts. Such is Tartt’s ability to display the vast emotional landscape of her main character.

As I said, I think that The Goldfinch is geared towards an audience of cynical and jaded adults. Not only does Tartt show readers how very little Theo is helped in tending to his emotional stability as a child, but also how this emotional state is carried on through adulthood. Tartt shows us the fast pace of the world and a man so caught up in it since he was thirteen that he must keep going or be overcome entirely, but by what? Theo acquired a painting, The Goldfinch, from The Hague on a day it was blown up. The explosion killed his mother and the painting serves as a metaphor for his emotions concerning her death—wrapped up tight in duct tape, a secret, hidden forever from himself and the world. The turnaround of the novel comes when Theo discovers that his friend Boris switched the painting for a magazine when they were kids and it has been sold to a person in Amsterdam. This metaphorically puts Theo in a place so distant from his feelings that he doesn’t even recognize them anymore—they are so far away that they are foreign.

Perhaps the ultimate criticism of American culture, therefore, is in the neat and risky resolution. Perhaps Tartt decides to “spell it out” for her readers because the point of the novel is to show how people have lost the emotional understanding to intuitively garner the meaning of the novel for themselves due to constant exposure to a culture that is too fast-paced, too dependent on drugs to drown out emotional problems, too distracted to feel—just like Theo. If this is the case, then the neat ending is the perfect ending to wrap it all up.

What makes The Goldfinch so brilliant, apart from the beauty in the writing itself, the complexity (and simplicity) of language, the depth of thought and emotion, is that by the end of an otherwise harrying tale, the reader feels relief, a sense of freedom from his or her own thoughts and the anxieties surrounding the belief that, “We don’t get to choose the people we are. Because—isn’t it drilled into us constantly, from childhood on, an unquestioned platitude in the culture—?”(761). And here, in this sense of relief, we understand why the book is named after and centered around a painting of a finch that is shackled to a perch by a chain drilled into a piece of wood by the culture of the man who maintained it.

Courtney Berti lives in South Lake Tahoe with her dog and her boyfriend, Kelley. She will receive her MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College by January 2015.

Courtney Berti lives in South Lake Tahoe with her dog and her boyfriend, Kelley. She will receive her MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College by January 2015.

Courtney Berti lives in South Lake Tahoe with her dog and her boyfriend, Kelley. She will receive her MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College by January 2015.

Courtney Berti lives in South Lake Tahoe with her dog and her boyfriend, Kelley. She will receive her MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College by January 2015.