Copyright © October 13, 2021

Copyright © October 13, 2021

Paperback/Poetry

$16.00/98 pp./5.5×8.5in

Steel Toe Books

ISBN 978-1-949540-26-0

Kaleidoscope Heart: A Response to Jenny Qi’s Focal Point by Sara Paye

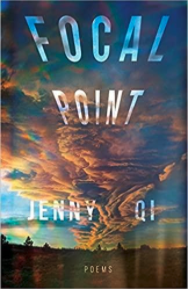

Jenny Qi’s Focal Point examines the intersections brought together by a dying loved one. The poet casts her heart into emotional and scientific detail, never allowing her vision to fully blur but rather focus and expand. The cover image shows a vacant landscape, the sky with sun-stricken clouds, the earth dark with shadows and trees. The clouds widen toward the cosmos, narrow toward the horizon, symbolizing the book’s namesake. Our narrator creates a memoir from lines of verse as her mother dies of cancer.

Throughout the work, Qi pays attention to her family, her parent’s DNA, and the expression of these elements within herself. She writes, “My father’s words a drumbeat. / She want to live, and you don’t let her. / I laid my head on her chest until her gown was wet” (16), and instantly the reader knows the father’s cadence, the mother’s pain, how Qi bears witness to both. A juxtaposition between family members becomes clear, created within just the first few pages of the book—as the author observes her father’s persistence for answers during her mother’s hospice. The reader will know the dynamic characters through Qi’s poignant and pointed words.

From the first page, Qi discusses a world where her concerns simultaneously converge and diverge: her future academic ambitions, those that will distract from, or inform, a future without her mother. Beginning with Brother, the narrator outlines her character’s shared desires with that of her mother, how those desires continue after the fact of death, how those desires are matched and pronounced by Qi’s understanding.

…how you swam out of her like a little fish

…how after that she clung to me harder

like a half-inflated life jacket.

I understood then why Mama and I

stared so hard at empty spaces, why

four felt so much happier than three. (Qi 22)

The tone is set. The poet will guide her reader through the following pages, gazing at empty spaces, treating vacancies as characters alike. A poem that exhibits the narrator’s broadening relational experiences and her desire to see and to be seen is We Will Die Beautifully in the Way of Stars.

I’d never heard anyone say he likes

the freckle on my left cheekbone,

the shameful flaw I tried to bleach out

and left my skin burning. (Qi 39)

When Qi’s connection with her mother is bound tightly, committed to memory, connections simultaneously form between the narrator and potential lovers. This is not an exchange of emotional ties. Instead, the reader gets to explore the channels and rooms of the poet’s heart, a kaleidoscope of bright intersections, each with its array of shadows. By Qi’s words, the reader will know grief is expansive. When reading One Year Later, we experience a compelling and sensory loss within the context of fine details. How these details create a season, construct a feeling, is a crucial aspect of Qi’s work.

I still can’t smell vanilla Chapstick

without smelling sickly sweet breath

stiff soiled sheets and alcohol hand sanitizer

hospital rations beneath maroon rubber lids (Qi 54)

Qi’s visceral experience supporting her mother echoes the tension between being needed among family and being wanted among lovers. Qi provides traces of the proof that a greater context to her character exists. When we once knew the flesh of love, we remember oceans of hindsight, waves blurry, salt fresh. Qi offers a gracious but acute poetic style in her phrasing that draws the reader close and captivates. Her use of balanced lines and adherence to some prose rules helps the reader pace herself, receive the content line by line. As seen here in Commonalities, In memory 06.12.16, this work details place, emotion, imagination, and reality.

It reminds me of Tennessee, pulses

melding with electric beats, dizzy

shimmying in a warm neon cocoon,

safe haven from little disasters.

All summer I tried to ignore my mother,

her neediness, so I could ignore my own. (Qi 69)

Qi pulls in, and the internal conflict presented by the narrator is heartbreaking, curious. It brings the reader right into the present moment of the poem, its issues, and its paradox. A perfect example of this is repeated at the end of Qi’s work here in Contingencies.

Clear my throat of dust again

these days inescapable. I imagine…

…how the ancients imagined us,

what it means to be immeasurable. (Qi 81)

Qi projects outward and expresses the title’s concept with poems varying from Dissonance and Daddy Issues to The plural of us and Dreaming of My Mother Five Years Later. Her poems are stories of deep and incisive searching. Qi’s style and emotion fill her poetry with relatability as the reader understands, expands as the reader wonders. Yet grief makes the heart a kaleidoscope and there is an opportunity to look within for the beyond. As with a frozen pond, or smoke escaping, Qi describes how the heart both expands and contracts with emotional and scientific proof.

*

Sara Paye (she/her) of Las Vegas, Nevada, is an awarded writer and Creative Writing MFA candidate at Sierra Nevada University. Paye’s published works are in Funicular Magazine and The National Women’s History Museum, among other locations. See their website at sarapaye.com.

Sara Paye (she/her) of Las Vegas, Nevada, is an awarded writer and Creative Writing MFA candidate at Sierra Nevada University. Paye’s published works are in Funicular Magazine and The National Women’s History Museum, among other locations. See their website at sarapaye.com.