Contact: June Saraceno

jsaraceno [at] sierranevada [dot] edu

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

(Incline Village, Nevada) Sierra Nevada College’s English Program has announced the winners of the 5th annual High School Writing Contest, a national competition which honors high school juniors and seniors in three categories: creative nonfiction, fiction and poetry.

The winners receive a cash prize, an invitation to the awards ceremony on Jan. 9, a scholarship offer from Sierra Nevada College, a private, non-profit four-year university in Incline Village, Nevada, and possible publication in the Sierra Nevada Review.

Bryce Bullins, managing editor for the Sierra Nevada Review said, “Selecting just a few winners from such a large pool was an especially difficult process considering the caliber of work these young writers submitted.”

Creative writing professors and Sierra Nevada Review staff evaluated a record number of submissions. Chosen from over 525 entries, the winning submissions came from students across the United States, including Maryland, Colorado, Florida, Arizona, and New Jersey.

“I am inspired and energized after reading these diverse and passionate stories. The future of the written word is clearly in good hands,” said Gayle Brandeis, the college’s Distinguished Writer in Residence and an award-winning novelist.

In creative nonfiction, first place went to Lindsay Emi, Westlake Village, California, for “Latin Class in Seven (VII) Parts.” Second place went to Darla Macel Anne Canales, Erie, Colorado, for “Oven.” Third place went to Gabriel Braunstein, Arlington, Massachusetts, for “Family on the Commuter Rail.” The nonfiction Local’s Prize went to Isabella Stenvall, San Luis Obispo, California, for “Wars with Numbers.”

Finalists in creative nonfiction were Emily Zhang, for “Family History,” Oriana Tang for “Sister,” Aletheia Wang for “Scar,” Jack Priessman for “A Merciless Deed,” and Annie Harmon for “Reflected.”

In fiction, first place went to Emily Zhang, Boyds, Maryland, for “Midwestern Myth.” Second place went to Lucy Silbaugh, Wyncote, Pennsylvania, for “Burrowing.” Third place went to Laura Ingram, Disputanta, Virginia, for “Absolute Value.” The fiction Local’s Prize went to Erin Stoodley, Ventura, California, for “Ghosts.”

Finalists in fiction were Lindsay Emi for “For My Daughter,” Jessica Li for “Ellen and Su-Ji,” Tatiana Saleh for “Laundry,” Madison Hoffman for “Genderfuck,” and Oriana Tang for “Lara.”

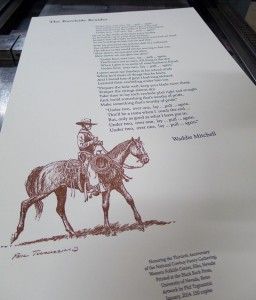

In poetry, first place went to Oriana Tang, Livingston, New Jersey, for “Bildungsroman.” Second place went to Catherine Valdez, Miami, Florida, for “Mami.” Third place went to Ruohan Miao, Chandler, Arizona, for “Dust Bowl.” The poetry Local’s Prize went to Ava Goga, Reno, Nevada, for “Notes on Repression.”

Finalists in poetry were Emily Zhang for “Transitory,” Katia Kozachok for “Primordial Roar,” Allie Spensley for “Palo Verde,” Emma Symmonds for “Purging,” and Jessica Prescott for “Daughter of Zeus, Lover of Mine.”

Winners in each category received $500 for first place, $250 for second and $100 for third. The Local’s Prize honored student writers from Nevada and California with a $100 prize. These students are also eligible for a $20,000 scholarship to attend Sierra Nevada College.

The winning students have been invited to read their work in an awards ceremony on Friday, Jan. 9, 2015 at Sierra Nevada College alongside highly acclaimed writers Suzanne Roberts and Alan Heathcock. They will be reading at 7 p.m. Friday in Sierra Nevada College’s Prim Library as part of the college’s low residency MFA creative writing program.

The Sierra Nevada Review’s annual issue publishes poetry, fiction, and nonfiction by emerging and nationally recognized authors. All High School Writing Contest winners will be considered for publication in the 2015 issue, which releases in May.

The 6th annual High School Writing Contest runs Sept. 1-Nov. 1, 2015. Guidelines can be found at https://www.sierranevada.edu/writer

is an aspiring writer and student at Sierra Nevada College. While Tom is an Incline Village, Nevada native, he has lived in both Washington and California. Tom enjoys writing creative non-fiction, climbing, fly fishing, and spending time with his wife, Andrea, and their dog, Munchichi.

is an aspiring writer and student at Sierra Nevada College. While Tom is an Incline Village, Nevada native, he has lived in both Washington and California. Tom enjoys writing creative non-fiction, climbing, fly fishing, and spending time with his wife, Andrea, and their dog, Munchichi.

is a Junior attending Sierra Nevada College as a Creative Writing major. He currently resides in Incline Village Nevada, but he is originally from Sacramento California. His focus is in fictional writing and has completed two novel manuscripts. One day he envisions himself not only writing books, but he wants to own two restaurants as well.

is a Junior attending Sierra Nevada College as a Creative Writing major. He currently resides in Incline Village Nevada, but he is originally from Sacramento California. His focus is in fictional writing and has completed two novel manuscripts. One day he envisions himself not only writing books, but he wants to own two restaurants as well. is an aspiring writer and student at Sierra Nevada College. While Tom is an Incline Village, Nevada native, he has lived in both Washington and California. Tom enjoys writing creative non-fiction, climbing, fly fishing, and spending time with his wife, Andrea, and their dog, Munchichi.

is an aspiring writer and student at Sierra Nevada College. While Tom is an Incline Village, Nevada native, he has lived in both Washington and California. Tom enjoys writing creative non-fiction, climbing, fly fishing, and spending time with his wife, Andrea, and their dog, Munchichi. resides on the north shore of Lake Tahoe in California but calls South Carolina home. She is currently a senior at Sierra Nevada College in Incline Village, Nevada. She will graduate with a Bachelors in English and a minor in creative writing. An avid hiker and nature enthusiast, Meredith can be found most days wandering with her pitbull rescue mix, Prudence, in Tahoe’s pristine wilderness. She also has a contemporary dance background and is an aspiring yogi.

resides on the north shore of Lake Tahoe in California but calls South Carolina home. She is currently a senior at Sierra Nevada College in Incline Village, Nevada. She will graduate with a Bachelors in English and a minor in creative writing. An avid hiker and nature enthusiast, Meredith can be found most days wandering with her pitbull rescue mix, Prudence, in Tahoe’s pristine wilderness. She also has a contemporary dance background and is an aspiring yogi. graduated from Sierra Nevada College with her BFA in Creative Writing. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing with an emphasis in fiction. She lives in South Lake Tahoe with her hairy boyfriend and her fuzzy dog who both have a tendency to resent her very hairless laptop.

graduated from Sierra Nevada College with her BFA in Creative Writing. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing with an emphasis in fiction. She lives in South Lake Tahoe with her hairy boyfriend and her fuzzy dog who both have a tendency to resent her very hairless laptop.