By Emily Provencher

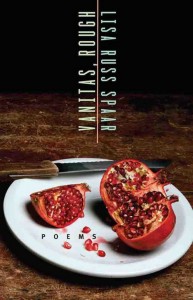

Publisher’s Weekly called Spaar’s latest work, “An entrancing world of lush language and passionate imaginings.” Vanitas, Rough features poems about the synchronicity of simplistic complexities in the often mundane face of everyday realities. In the piece, “Trailing Mary & Martha: 3 AM,” Spaar speaks of “unfathomable barking / [and] jaw dumpsters in the cul-de-sacs.” Not the craziest of poetic happenings, but written with poise and understanding.

The first time, I read this entire book of poetry without having any idea of what the title of the collection meant, or how the cover image related to the work inside the bind. I thoroughly enjoyed this collection of poems, and then I decided to look up the definition of the word “vanitas.” It is, “a still-life painting of a 17th-century Dutch genre containing symbols of death or change as a reminder of their inevitability.” (google.com) The pomegranate is a symbol of fertility and abundance in some sects of mythology, especially Greek and Roman. The cover of this collection alone is a beautiful metaphor representing the inevitable rising and falling of abundance and goodness versus the bleakness one encounters throughout different periods of time.

“the shear, the jabbing jaws / in elbow high gloves / & up to the briary cervix, a welter historical,”

A line from one of the early poems, “Old Rose,” had my mouth watering for more sublimely tantalizing words. The overall content of this series of poems is of nothing truly shocking or out of the ordinary, but is still wonderful to read. The language Spaar uses throughout her poetry is astounding.

“Vanitas, Rough” features the hypnotizing lines, “your tongue in me is mine, too… / drunken wasp grazing semen yolk / of split, glazed oyster shells, / Death blowing soap bubbles / out the orbital sockets…” These phrasings captivate readers due to their close-to-absurd wording. They force the reader to go back and read the line over and over because of the terrifically strange content.

It can be difficult for authors to eloquently capture the banality of longing. In Vanitas, Rough, Spaar calls to Emily Dickinson as a muse in “Spring Fever” and “Outliving Emily,” channeling the metric empress of the nineteenth century in her lines of carefully constructed syntax in her pithy diction throughout this series.

The language in this collection is beautiful, but when I was finished reading the book, I did not find myself changed or moved from the experience. Nonetheless, Vanitas, Rough is a beautifully written catalogue of poetry and it is very enjoyable to read.Spaar uses words to illustrate a bizarre myriad of alluring images in her latest publication, it is a great work that writers and readers alike will appreciate.

Author Bio:

Emily Provencher is a twenty one year old english major focusing on poetry at Sierra Nevada College in North Lake Tahoe. Originally from Southern New Hampshire, she moved to California for all the wrong reasons and is still absolutely relishing her decisions to move west three years later. Emily enjoys pondering the mysteries of the universe, drinking Guatemalan coffee, mining for precious stones, reading Tarot cards, cultivating and sustaining of the miracle life from the Earth, and reading and writing poetry with any and all chances she gets. She is new to editing and blogging, but having a pen in hand is simply second nature to her. Emily accepts all criticisms to her work, but she will also not hesitate to criticize yours.